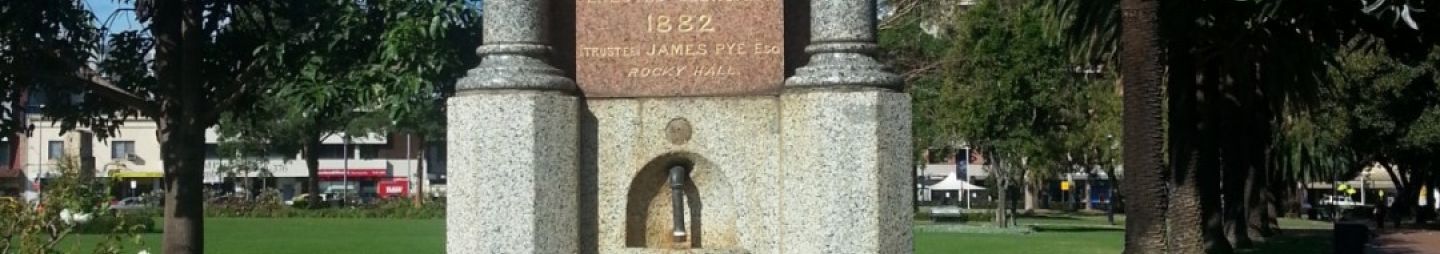

The Anderson Fountain – Photo Peter Arfanis

Mathew Anderson (ca. 1790-1850): ‘Dr Anderson’, wrote Mrs Elizabeth Macarthur, ’was related to the Percy family of the Duke of Northumberland’. At some time he trained at the College of Surgeons at Edinburgh, and then entered the Royal Navy in 1809 and was appointed surgeon in 1814. He transferred to the Medical Service in Sydney in 1824 apparently when he arrived on the Castle Forbes in 15 January 1824.[1]

When Mathew Anderson was posted to Parramatta in 1827 as an Assistant Colonial Surgeon in charge of the relatively newly built hospital to succeed Dr Allen, he was no stranger to the colony.He had first visited Australia as surgeon of several convict ship’s. His first voyage was on the Surrey (3), a 443 ton ship built at Harwich which left in late August 1818 from Sheerness. The Surrey, on which only three deaths occurred during the journey, arrived in Sydney, via Rio de Janeiro, in March 1818, after 156 days under the ship’s master Thomas Raine. [2] Anderson’s second journey as ship’s surgeon superintendent was on the Mangles , its first journey to Australia. A larger ship of 594 ton, it was built in Bengal, India in 1802 a under the master, John Cogill, having left Falmouth in April 1820, sailing direct to Sydney arriving on 7 August after a fast voyage only 118 days later, having only recorded one death aboard .[3] Another journey was made on the Mangles (2) under much the same time and conditions arriving in November 1822. Seafaring surgery must have agreed with Anderson as he made a fourth and last voyage on the ship Castle Forbes (2) out of Cork under master John Ord in the spectacular time of 109 days in a smaller ship of 439 ton, again having recorded only one death on the voyage.[4] The conclusions are that Anderson was an excellent doctor to the convicts and the masters more humane than in earlier days.

Anderson found the environment at Parramatta to his liking and temperament, allowing him to settle permanently in the town. Keith Macarthur Brown wrote:

He was an outstanding example of a cultured English gentleman whose sterling qualities of mind and character were unstintingly devoted to the services of others and whose influence helped to develop the country upon sound British lines.[5]

Anderson, like most doctors in the colony, was appointed a resident magistrate, a position which he filled for eighteen years with impartiality and discretion, earning an enviable reputation for his zeal. He was a keen churchgoer, becoming a pillar of St John’s congregation. Anderson was prominent in all social and political activities, such as the emerging municipal government and farming his recreation, aspects of which will be expanded later. His first duty however was always to his medical work and the hospital. He was always able to cope with the demands on his professional time, his ‘practice’ covering some 600 square miles and included the government institutions of Parramatta such as The Female Factory and the Female Orphan School. Parramatta residents found that despite his zeal, Anderson did not have the time to attend to the needs of this growing community and the expanding needs for medical attention. This problem was greatly eased with the return of the native son, Dr. William Sherwin, who returned to his home town after twelve months in the north of the country.[6] In addition to his normal duties, he attended Governor Bourke and his family when they were in residence at Parramatta in the 1830s.

Anderson’s workload led to a deterioration in his health and optimistically, he applied to the Medical Department of the Navy in 1837 for permission to retire on half pay but was refused. He took leave of absence in June 1838, retiring at the end of the year on grounds of ill health.[7] Undeterred by the government’s refusal for a pension, he kept up a steady correspondence with the Department until in 1845 he was granted ‘a retiring allowance of £110 per annum in view of his impaired state of health and the governor’s assurance that he derived little or no emolument from private practice’.[8] During Darling’s governorship, from 1828, the Colonial Medical Service had been reorganised and was attached to the Department of Convicts. Anderson had been promoted to the position of Surgeon from 1 January 1829 with a salary increase to £273.15.0 per annum from £136.17.0. The promotion would have also raised the status of the hospital.[9]

Association with the hospital: On 28 March 1848, The colonial Hospital at Parramatta was without any convict patients for the first time in its turbulent history as a result of the cessation of transportation to NSW.[10] The remaining female patients had been placed in the Female Factory while insane patients were transferred to an asylum (Tarban Creek?). This situation had been known for some time and had been under discussion by the District Council, of which Anderson was an active member.

For some weeks prior to the closure, Drs Anderson and Hill had been negotiating with the government for the appropriation of the hospital buildings, furniture and fittings, for the benefit of the populace of Parramatta. On 28 March 1848, an open meeting attended by people of the town and adjoining districts had been held in the Court House and had inaugurated a movement to present a petition on Governor Fitzroy ‘praying that the old convict hospital be now converted to public use’. A reply from the Colonial Secretary was read to the next public meeting on 6 May 1848, confirming that the transfer of the building, furniture and stores would be approved on the understanding that the institution would be under the proper control and management of ‘a committee of gentlemen’ elected by the community. In addition, an offer of a grant of an annual subsidy of £200 would be made provided that an equal sum was raised by private contribution or patients fees.[11]

This presented no problems to the organising committee and the first Committee of Management of the Parramatta and District Hospital (as it was to be known in the future) was elected at a public meeting on 6 May 1848, comprising G. Eliott Esq, HH Macarthur Esq, M. Anderson Esq, J. Blaxland Esq, G. B. Suttor Esq, N. Lawson Esq. and Messrs J. Edrop, J Houison, J. Byrnes, G. Oakes, J. Hamilton, M. McKay and S. Phillips. This gave an imbalance of seven plebeians to six gentlemen but the governor approved the committee. At the first committee meeting on 8 June, Dr Anderson was elected president, James Houison, Treasurer and Samuel Phillips, Secretary. Drs Robertson and Hill consented to become the first Honorary Medical Officers.[12]

Farming interests: Like other professional men of the transportation era, he became interested in farming and acquired land between Goulbourn and Braidwood in 1825, naming it Redesdale. Over the next ten years ‘a substantial cottage, store, granary, barn and other buildings’ were built. The house was a simple four roomed weatherboard structure with hipped roof and verandahs to the front and back and apparently is still standing today. Anderson sold the property in 1835 to Hugh Gordon who had married Mary, third daughter of Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur. The Gordons renamed the property Manar and added a more substantial house to it. Mary’s parents lived here for a time after Macarthur’s empire eventually crumbled in 1848 due to the 1842 financial crisis.[13]

Anderson’s political interests: Anderson became friends with Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur, John’s nephew, who was a fellow magistrate on the Parramatta Bench. Even though Macarthur was elected unopposed, Anderson had the honour of officially nominating him at the hustings at Parramatta Court House in June 1843 as the representative for Parramatta in the first election for the semi-elective Legislative Council. Macarthur’s nomination was seconded by Dr William Woolls, another friend with whom they encouraged the erection of the new church in North Parramatta, All Saints’.

Gilbert Eliot, the Parramatta Police Magistrate, was requested by the governor early in 1843 to nominate a list of local citizens whom he considered worthy as nominees for the new District Council to be formed in the town. Amongst the gentlemen nominated were the town’s magistrates and naturally included Anderson. Gipps accepted the nominations but many gradually lost interest. However, in 1844 when Parramatta voters were given the opportunity to elect their District Council, Anderson was re-elected along with many of the town’s active citizens, such as James Houison, George Oakes, James Pye, Nathaniel Payten and George Nichols.[14]

A number of these men, including Anderson, were elected to a Select Committee of the Council to investigate the possibilities of erecting a dam for a new water supply. It had been a practical dream of Anderson who thought it necessary for the town to have an ample supply of pure water throughout the town. He had become increasingly aware of the danger of the polluted water supply of the Town Dam, suspecting it to be the cause of many of the epidemics that plagued the inhabitants, particularly the children. He worked tirelessly with Houison, Pye and Payten as the town’s Water Commissioners towards the project on Hunt’s Creek at North Rocks but was not to see its completion.[15]

His relationship with John Macarthur’s family: In March 1827, Elizabeth Macarthur, always keeping her children living overseas aware of their father’s health, wrote to her son John in London:

There is a worthy man at Parramatta that has charge of the hospital there, Dr Anderson RN. He visits your father daily and quite understands the nature of his complaints.[16]

and some time later

… he spent the evening in conversation, sometimes sportive, sometimes argumentative, with Dr Anderson (a plain, sensible worthy man who generally visits us every evening) …[17]

Anderson became a firm friend of the Macarthur family and was known affectionately as ‘Mr Andy’, often visiting Camden with William. Elizabeth Macarthur’s confidence in Anderson as a doctor prompted her to seek his services in her later years in life. It became her practice, starting in 1847, to spend some of the summer months at Watson’s Bay, to escape the hot seasonal weather at Parramatta. With her daughter Emmeline, servants, bags and baggage, they would travel down river by steamer to the Parker’s house Clovelly, at Watson’s Bay. Emmelene’s husband, Henry Watson Parker, had purchased Clovelly from Hannibal Macarthur when he was experiencing financial problems during the days of the depression. A constant visitor to Clovelly was Dr Anderson, who had been living for some years since 1839 in part of the Macarthur Cottage close to Elizabeth Farm (now known as Hambledon Cottage) to be able to attend the family. It was in February 1846 that Elizabeth wrote to her son Edward advising him that Dr Anderson still resided in the cottage ‘which with the garden and little paddock he keeps in perfect order’, living there in comfort and respectability.[18]

In 1849, along with Emmeline and her husband and Dr Anderson in the ‘house party’, summer was spent pleasantly at Clovelly. In the following year, the holiday was repeated with the same group, but late during their sojourn, Mrs Macarthur suffered a stroke and it was here, attended by her friend and physician, that she died on 9 February 1850 at the age of 83 years.[19]

His last years: Anderson had apparently vacated his rooms at The Cottage by August 1847 and he had moved to a new residence he had built at Parramatta.[20] Keith Brown includes an illustration titled ‘Dr Mathew Anderson’s house in Macquarie Street, Parramatta’ in his history. Some confusion exists here as the house, Edgeworth, was always considered to have been built by James Houison for James Byrnes of Edgeworthstone, Ireland but there is firm evidence that his friend James Houison built the house.[21]

Three months prior to his death while Anderson was acting as magistrate on the Parramatta Bench, he suffered a sudden seizure. Quietly he retired, giving no explanation for his actions. The counsel for the defence, unaware of his illness, became abusive and protested on his client’s behalf, claiming that Dr Anderson’s sudden absence would prejudice his case. Anderson had learned from John Macarthur, in the years which he attended him, to conceal his disabilities.[22] His last days in hospital were lonely as he had no family, although his many friends would have visited him. It was James Macarthur however who sat at his bedside during his last hours, out of respect for the kindnesses shown by Anderson to his aging parents in their last years. A few months later James wrote to his wife Emily of their old friend ‘of sterling goodness although mixed with some right worthy alloy’.[23]

Matthew Anderson was buried by the Reverend Henry Bobart in St John’s Cemetery and his simple sandstone altar grave marker records ‘ANDERSON, Matthew, Esq. / Surgeon in the Royal Navy / 7 July 1850’. The only decoration on the stone was a small stylised anchor. The burial register record his occupation as ‘gentleman’.[24] The legacies in his will recorded his great interests in Parramatta. He bequeathed £300 his hospital, his name may still be seen heading the list of donors on the honour board which in itself is a small history of Parramatta. Even a few years after his death when the hospital was struggling financially, this bequest was most appreciated. To his church, St John’s, where he was a churchwarden for many years, he left a substantial amount. Another large bequest was made for the erection of public drinking fountains in the central portion of the town. [25]

The drinking fountains: As trustees to administer his bequest and erect the drinking fountains, Anderson had nominated his friends, the Water Commissioners of the District Council, James Houison, Nathaniel Payten and James Pye. With the great delay in the reticulation of water from the dam to the town, it was not until May 1882 that the last remaining trustee, James Pye of Rocky Hall was able to comply with the bequest. The Mayor, Alderman CJ Byrnes dedicated the first fountain which was erected on the south-east corner of George and Macquarie Streets. Unfortunately, a later corporation moved the fountain in 1888, to replace it with the Centenary Fountain, resulting in the fountain being installed in the north-east corner of Prince Alfred Park. Communities are apt to recognise new heroes and forget the old and in the 1930’s the fountain was displaced by the Gollan Memorial Clock and the ‘curiously shaped fountain’ was moved to the park’s north-west corner, near St Patrick’s Cathedral.

It is believed that ten other fountains were erected afterwards in locations such as the south side corner of Pitt Row and Macquarie Street, at the entrance to the George Street Park Gates and one in George Street. [26]

Anderson’s death was mourned by those who remembered his contribution to the town. A street was named for him in South Parramatta and when in 1868 the four Parramatta wards were named by Council, Anderson was linked with pioneers Marsden, Gore (prominent Minister at All Saints’ Church) and Forrest (prominent Headmaster at The King’s School). Again, a later Council, never prominent in remembering the city’s heritage, recently saw fit to forget the town founders and rename the city wards.

Dr Keith Brown in his annals of the medicos of Parramatta wrote:

Anderson was a man of culture, commonsense and refinement; courteous, calm and dignified in manner, he was imbued with a deep sense of his obligation to the community to which he proudly belonged. To him, his religion was dear. [27]

Anderson’s replacement was a surgeon, James Eckford, who remained only six months at the hospital. He was followed by Kinnear Robertson from 1840 to 1844 who in turn was succeeded by Dr Patrick Hill. Meanwhile, Dr John Cates set up in the town.

by John McClymont, Parramatta Historian, April 1999.

From the manuscripts donated to the Parramatta Heritage and Visitor Centre, 2014

![]()

Neera Sahni, Research Services Leader, Parramatta Heritage Centre, City of Parramatta, 2020

References:

[1] Anderson Papers, ML A821.

[2] C. Bateson, The Convict Ships, Glasgow, Brown Son and Ferguson, 1969, p. 341; Thomas Raine was a brother of John Raine, the founder of the Darling Mills in North Parramatta.

[3] C. Bateson, The Convict Ships, p.342.

[4] Ibid, pp. 344-45.

[5] K. Brown, Medical History of Old Parramatta, pp. 24-5.

[6] Ibid, pp. 24-5.

[7] B. Horton (ed), Caring for Convicts and the Community, p. 23

[8] K. Brown, Medical History of Old Parramatta, p. 37.

[9] B. Horton (ed), Caring for Convicts and the Community, p. 22.

[10] This was as a result of the recommendation of Molesworth Committee of Enquiry to the British Parliament in 1840, that penal transportation to Australia should be limited to Norfolk Island and VDL.

[11] B. Horton (ed), Caring for Convicts and the Community, p.30.

[12] Ibid p.31; K. Brown, Medical History of Old Parramatta, pp. 40-41.

[13] R. Roxburgh, Early Colonial Houses of New South Wales, Sydney, Ure Smith, 1975, p. 557.

[14] FA Larcombe, Origins of Local Government, in NSW, 1831-1858, Sydney, SUP, 1973, vol. 1,

pp. 202-209; Eliot to Col Sec, 21 Mar 1843, AONSW;

[15] WV. Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, Sydney, MWS &DB, 1961, 83-7.

[16] MH. Ellis, John Macarthur, Sydney, A &R, 1969, p. 201 – Elizabeth Macarthur to John Macarthut Jnr, 7

Mar 1827, ML A2906.

[17] MH. Ellis, John Macarthur, pp.526-7.

[18] Elizabeth Macarthur to Edward Macarthur, 27 Feb 1846, ML A2907.

[19] H. King, Elizabeth Macarthur and her World, Sydney, SUP, 1980, pp. 202-204.

[20] J. Hughes, ‘Hambledon Cottage Parramatta, Historical Documentation to 1965’, report prepared for

Parramatta City Council, 1996, p.45.

[21] Hughes does not mention Anderson’s new address, it was in Macquarie Street, now demolished.

[22] K. Brown, Medical History of Old Parramatta, pp. 43-4.

[23] Macarthur Papers, ML. 9 Jul 1850 ,A4343.

[24] J. Dunn, (ed) The Parramatta Cemeteries, St John’s, p.87.

[25] K. Brown, Medical History of Old Parramatta, p. 42.

[26] TD Little (ed) Fuller’s 1885 Central Cumberland Directory, Parramatta, 1885, pp 102-3.

[27] K. Brown, Medical History of Old Parramatta, p. 43.